Early Historic Indians of The Warrior Mountains

De Soto's 1540 Invasion of North America

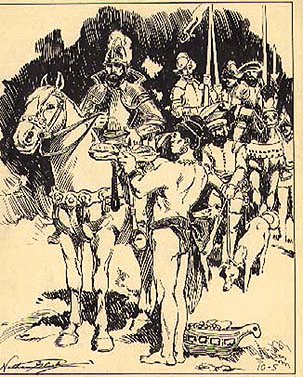

Hernando De Soto, a Spanish explorer, was the first European to move inland to the heart of Indian country. De Soto had been with Cortez in Mexico when he conquered the Aztec and became a very rich man. He was also with Pizarro in South America when Pizarro robbed and killed many of the Incas. De Soto's goal was to conquer the southeastern Indians, steal their gold and become a very wealthy man just as they.

On June 28, 1540, De Soto crossed the Tennessee River and entered Alabama. He was the first European to discover the Tennessee River. De Soto entered Alabama in Jackson County and crossed the Sand Mountain. US Hwy 72 from Bridgeport toward Scottsboro in Jackson County follows near the route which De Soto used on the first leg of his exploration. From June 1540 until December 1540, De Soto traveled through Jackson, Marshall, Etowah, St. Clair, Calhoun, Talladega, Coosa, Elmore, Montgomery, Autauga, Lowndes, Dallas, Wilcox, Monroe, Clarke, Marengo, Hale, Greene, and Pickens Counties of Alabama.

The Federal government appointed a commission of scholars to make a detailed study of De Soto's route to clarify the contradictions that have arisen about his exploration. Dr. Walter B. Jones was secretary of the commission. The Final Report of De Soto Commission was published in 1939.

De Soto's party consisted of about 600 men, in addition to numerous Indians who went along as guides, laborers, and bearers of burdens. In De Soto's army, there were a number of Portuguese and a mixture of other nationalities, although most were Spaniards. De Soto brought Negro slaves into Alabama which were probably the first Negroes to enter Alabama. With De Soto came a few high born nobles and many plain men including artisans of various trades: carpenters, shoemakers, tailors, blacksmiths, swordmakers, soldiers, seamen, and priests. De Soto obtained food by seizing it from the Indians who had stored up small amounts for their own use.

At Tali, De Soto crossed the Tennessee River for the third time and entered the Indian village of Coosa. Coosa was the center of a prosperous Creek Indian agricultural complex. The Indian village of Coosa was located near the present day Childersburg. Coosa was the upper of the two capitols of the Creek Indians. Today, one would pass through or near De Soto Country while traveling to the following cities: Albertville, Atalla, Gadsden, Talladega, and Childersburg. It was De Soto's custom to seize Indian chiefs who were then held hostage to ensure that De Soto got what he wanted.

On August 20, 1540, De Soto's men left the village of Coosa and on August 31, they arrived at Ulibahali. Ulibahali was located on the north side of the Tallapoosa River. Ulibahali was about halfway between the big bend in the Tallapoosa and the point where it joins the Coosa River between Montgomery and Wetumpka. From Ulibahali, De Soto and his men went to Talisi, the northwestern edge of present day Montgomery where Maxwell Air Force Base now stands.

It was at Talisi that De Soto encountered the son of Chief Tuscaloosa; therefore, he released the Coosa chief who was being held hostage. Leaving Talisi, the Spaniards proceeded through present day Dallas County near the mouth of Cedar Creek. From here, De Soto moved southward to Camden and through Wilcox County into Monroe County to the Indian village of Piache. The Spaniards moved from Piache to Mabila, one of the most important places to De Soto's men and to Alabama History.

At Mabila on October 18, 1540, was fought one of the bloodiest battles with and Indians on American soil. De Soto was living on the spoils of the land since his supply base was in Cuba. The Indians were anxious to protect their winter food supply. The Spaniards were willing to fight the Indians because they had armor to protect themselves from the Indian arrows. The greatest advantage of all advantages was the fact that the Spaniards had horses. It is very unlikely that even a determined man like De Soto would have tried to crack the hard problem of the Alabama wilderness if the Spaniards had not so many advantages over the Indians. In the Battle of Mabila, the Indians were led by Chief Tuscaloosa, a giant of a man. Since Tuscaloosa means Black Warrior, the river bears his name. De Soto tried to win Chief Tuscaloosa's friendship by giving him presents such as a scarlet suit, cap and the largest horse he had. In spite of De Soto's outward show of friendship, it soon became clear to Tuscaloosa that De Soto intended t make him a prisoner.

When the Indians realized that Chief Tuscaloosa was a prisoner, they were ready to fight. It was a fierce battle that lasted all day. When it became clear that the Spanish were winning, several Indians committed suicide. The Spaniards set fire to the Indian village. De Soto was wounded and about twenty Spaniards and an estimated 2,500 Indians were killed. Although wounded, De Soto continued his journey toward the Gulf of Mexico to meet with Franciso Maldonado, who was bringing fresh supplies. Because De Soto had not succeeded in finding gold and could not accept defeat, he decided to move northward away from Maldonado. De Soto remained at Mabila from October 18 to November 14, 1540, to allow his men to recover from battle. Although De Soto never found the gold he so desperately sought in Alabama, De Soto became one of the most famous explorers anywhere in the world.

De Soto departed Mabila on November 14, 1540, and moved northward to the Black Warrior River. The country he traveled is today US Hwy 43 from Grove Hill to Thomasville, Dixons Mill, Linden, and Old Spring Hill. From Old Spring Hill, De Soto passed a few miles east of Demopolis toward Greeneburg and crossed the Black Warrior River where he found four Indian villages. From these villages, De Soto moved north and then west through present day Eutaw in Green County, and from there across the Sipsey River. They passed near Carrolton in Pickens County and moved across the present day Alabama state line into Mississippi.

De Soto was the first European to discover the Tennessee River, the Coosa, the Tallapoosa, the Alabama, the Black Warrior, the Sipsey River, the Tombigbee, and many lesser creeks and streams of Alabama (Summersell, 1981).

Diseases Transmitted by Europeans

New world diseases were among the greatest killers of Southeastern Indian people. Epidemics of lethal pathogens began to spread widely through the Native American population no later than A.D. 1520 and did not end until 1918 (Dobyns, 1983). The devastation of disease helped break the power of Native Americans and left them vulnerable to cultural change brought by invading Europeans.

When Europeans came to the New World they brought several diseases for which the Indians had no immunity. The first meeting between Europeans and Southeastern Indians for which we have adequate documentation came in 1513 with Ponce de Leon on the Florida coast. Indians contracted diseases from sailors whose European ships briefly touched the coast or from shipwrecked sailors. In 1521, a party lead by a captain came ashore in the vicinity of Winyaw Bay, South Carolina where the Indians were invited to visit the ships and were promptly enslaved. Many of the enslaved Indian prisoners on the ship fell ill and died. When De Soto reached Cofitachequi in central South Carolina he found whole villages wiped out because of the epidemic. Confitachequi was one of the most impressive Indian societies that De Soto witnessed. The town itself was deserted because of depopulation caused by the plague.

The Paleo ancestors of the Southeastern Indians left the diseases of the Old World behind; but when the Old World diseases reached the New World shores, the Indians met with disaster. The most lethal pathogen Europeans introduced to Native Americans in terms of the total number of casualties was smallpox (Dobyns, 1983). Smallpox was the most terrible of the new diseases. Other diseases included measles, typhus, tuberculosis, chicken pox, and influenza. Europeans had been exposed to these diseases for many centuries and had acquired a resistance to them so they usually recovered. Smallpox is extremely communicable, especially under crowded conditions. Among the previously unexposed New World population, small pox would infect almost every individual and 30 percent or more of those infected would die. After an incubation period of about twelve days, the victim of smallpox suffers from high fever and vomiting, and three or four days later his body becomes covered with skin eruptions. For those who survive the disease, the eruptions dry up in about a week or ten days and the scabs fall off leaving disfiguring pockmarks. Some Indians were made blind by this disease. People who survive are immune for a period of time (Dobyns, 1983).

Measles, also caused by a virus, may have been the second largest killer of Native Americans. Spaniards transmitted this scourge of disease to Native Americans in 1531. Thousands of these natives died because they contracted measles when they were pressed into service. Between 1530-1900, there were at least 15 epidemics of measles. Influenza may have been the third most lethal disease of Native Americans. At least 10 influenza epidemics or combinations of influenza and other diseases caused many deaths. A combination of influenza with smallpox or with another rash-producing virus caused extremely high mortality.

Bubonic plague vied with influenza as the third largest killer of Native Americans. The Black Death that had terrified Europe reached the New World in 1545 and was transmitted to man by fleas that lived on rats. There were four epidemics of the plague between 1545 and 1707.

Diphtheria caused by bacillus, became epidemic on at least five occasions during the 17th and 18th centuries causing tremendous numbers of deaths. Typhus, a deadly rickettsial disease, was difficult to diagnose prior to the mid-nineteenth century. Ship's typhus was common among crews and passengers on European sailing ships carrying people and goods to the New World. There were four documented epidemics and other probable ones between 1580-1740.

During the 19th century, Native Americans suffered with immigrant Europeans from world cholera epidemics in 1832-1834, 1849, and 1867. Cholera was transmitted by water infected by the disease germ. US troops often transmitted the disease to Native Americans.

Scarlet fever was not identified by the medical profession as a distinct affliction until the 18th century. Other diseases of lesser significance among Native Americans were whooping cough, malaria, and mumps. There are also indications that Native Americans suffered from diabetes (Readers Digest, 1978).

Trade between Southeastern Indians and Europeans

Trade between Europeans and Alabama Indians was based largely on the barter on animal skins (furs and hides). An Indian could swap 30 deerskins for a new rifle. With rifles obtained through fur trade, the Indians in Lawrence County and North Alabama became more proficient in killing game.

Native animals such as whitetail deer, black bear, eastern elk became depleted throughout the Southeastern United States. The commercialized fur trade with the Indians and afterward with early settlers lead to the extirpation of these magnificent animals from Lawrence County and North Alabama by the early 1900's.

European trade with the Southern Indians opened a new ear in American history. Southeastern Indian trade was mainly among the countries of Spain, Britain, and France. Trade with the various European countries was seperated geographically. Spain controlled trade in Florida and surrounding areas. France controlled trade in Louisiana and the Mississippi River area. Britain controlled trade in the Atlantic coast area.

The main items of trade were deerskins and Indian slaves. In the short term, the trade in deerskins and Indian slaves was a way in which the British could market some of their manufactured goods- guns, tomahawks, hoes, brass kettles, knives, rum, beads, hawk bells, and cloth. In the long term, it was their way of reducing them to dependent status and of disrupting and destroying them. The Indians found that they could not exist without cloths, tools, and ammunition. As the traders became economically necessary to the Indians, they found they could manipulate the Indian. The traders lived dangerous lives; more often than not the Indians hated them. Spurred by economic necessity the Indians very rapidly depleted the deer population.

From 1699 to 1715, Carolina exported an average of 54,000 deerskins per year. The greatest number of deerskins in any one year was 121,355 in 1707. In addition to trading for skins, Southeastern traders continued doing business in Indian slaves. In 1708, the total population of South Carolina was 9,580 including 2,900 blacks, and 1,400 Indian slaves. In 1712, an Indian man or woman sold for 18 to 20 pounds. The French justified Indian slavery on the ground that it saved them from cruel deaths at the hands of their enemies.

The Yamasee War, caused over trade, was a widespread revolt against the Carolina traders by the Creeks, Coctaws, some Cherokees and some of the Indian who lived along the Savannah River. Because of the war, the Indians found themselves in debt. In 1711 an estimated debt to the traders amounted to 100,000 deerskins; this meant that each male Indian found themselves in debt for about two years of his labor. The deerskin trade crumbled during the hostilities and it was not fully rebuilt until 1722. After the war, British power waned and French and Spanish power was enhanced. The Lower Creeks allowed the French to build Fort Toulouse on the Alabama River in 1717. Unlicensed traders "the lowest people" used rum to get the Creeks and Cherokees drunk and then cheated them out of their deerskins (Swanton, 1987).

Early Populations Estimates for Southeastern Tribes

Early population estimates based on census records of the foue major tribes of the Southeastern Indians are inaccurate since the records did not declare the degree of Indian blood necessary for a person to be an Indian. Many mixed-blood Indian people avoided census records because the first Indian census was for enrollment for removal and for appraisal of their property. Therefore, the 1832 and 1835 Indian census records missed many mixed-blood people who were one-quarter or less Indian because it was very unpopular to be declared Indian. Even the President of the United States showed open dislike of all Indian peoples.

After Indian removal in 1838 it would have been very foolish for a mixed-blood Indian person in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia to declare himself an Indian. The post removal period was a time for mixed blood Indians to deny their race unless they were willing to give up all they had and be placed on reservations. The Cherokee population ranged from 22,000 in 1650 to 22,804 in the "1835 Census of the Cherokee Indians east of the Mississippi." The Choctaw population ranged from 15,000 in 1650 to 15,911 in the 1910 Census. The Chickasaw population ranged from 8,000 in 1650 to 10,956 in 1919 in 1832-1833 Census.

The Removal of The Warrior Mountain Indians

For some 12,000 years prior to the early 1800's, the entire area throughout the Warrior Mountains was inhabited, controlled, and ruled by our aboriginal ancestors. Through the early European explorations of De Soto in 1540, other adventurous expeditions/military campaigns, and encroachments by early settlers, our native people were weakened by the ravages of disease and wars that wiped out entire villages and towns. The tragic stage for the decimation of our Warrior Mountain Indian people was finally set after some 275 years of fighting these diseases and wars brought about by the greed of the European settlers.

The High Town or Ridge Path followed the east-west Continental Divide through the Warrior Mountains and was occupied home lands of the Chickasaws and Cherokees around the 1750's. Long before their occupation, the Tennessee Valley was claimed as hunting territory for both tribes. The southern drainages of the Divide were occupied by our Creek ancestors when De Soto marched his army through Alabama in 1540. It was the lands in the heart of the Warrior Mountains that Creek people had called home for hundreds of years.

Finally, our native people began to crumble from the European onslaught and pressure. The first native lands of the Warrior Mountains were threatened by the Cotton Gin Treaty of 1806. Later, the Treaty of Fort Jackson in 1814 took all our Creek homelands in the Warrior Mountains, south of the High Town Path. Within two years, the Turkey Town Treaty of September 16 & 18, 1816, had taken the last remnants of our aboriginal ancestors' native lands in the Warrior Mountains. The following years of forced removal decimated our native people, who had lived for thousands of years in harmony with the land of the Warrior Mountains.